On catastrophic risks from AI

Q: “You have views on artificial intelligence. Tell us about them.”

AI has developed at an extraordinary pace, and as it develops it will cause fundamental changes, just as the technological developments of the last few centuries have fundamentally transformed the world. AI thus has the potential for enormous benefits, as well as harms. Unfortunately, there are many unresolved problems associated with AI safety, making catastrophic outcomes a very realistic possibility.

Q: “We’ll get into the details in a moment, but do you have a brief description of what these views are based on?”

Here are key ideas in short:

- AIs can become extremely capable, thus creating serious risks.

- This is the direction in which the current AI industry is rapidly heading.

- We have very poor understanding of how AIs function.

- Many problems are not visible on the surface: on the contrary, various factors lead to problems being hidden.

A one-sentence version: ‘We’re building AIs that are more capable than humans without really understanding what we’re doing, and this might be a bad idea.’

Q: “What kind of topics will be covered?”

- A brief overview of artificial intelligence. What’s AI all about?

- The dangers of AI. How can AI be dangerous?

- Timelines. When will these dangerous AIs be built, if ever?

- Level of understanding. What do you mean we don’t understand how AI works?

- Hidden problems. Why are problems difficult to detect and fix?

- Goals. Do AIs have goals?

- Concrete stories. How is the situation developing?

- Solutions. What can be done?

A bit about the nature of the text:

The target audience of the text is people who want a technical understanding of the risks posed by AI systems. I’ve aimed to make the text accessible to a general audience, but especially towards the end I will go through detailed and technical ideas about current AI.

For the reader who instead wants a shorter, high-level description of the risks of AI, I suggest reading Daniel Eth’s article AI Alignment, Explained in 5 Points. And for the reader who wants more focus to the interaction of AI with society, from systematic risks to misuse, I recommend the article An Overview of Catastrophic AI Risks by Dan Hendrycks, Mantas Mazeika and Thomas Woodside.

If, on the other hand, the reader wants to understand why AI itself poses risks and why these risks are difficult to mitigate, my answer is below – with the caveat that I have tried to write accessibly and relatively briefly.

Translated from the original Finnish version from March 2024. The translation might have shortcomings.1

1. About AI in general

Q: “Let’s start from the very beginning. What is this ‘artificial intelligence’ you speak of?”

Humans have the ability to observe and model their environment, learn, solve all kinds of problems, plan for the future, and so on. Something happens in our brains that makes all this possible, and some may refer to it as ‘intelligence’ or ‘cognitive ability’. Although humans (and to varying degrees other animals) have these abilities, we still don’t really understand this phenomenon.

The goal of the AI field is to make computers do the same things: to create a program that can also learn, solve problems, design and model the environment.

Q: “How would you describe the situation in AI in general?”

The last decade has seen an explosion of developments. Approaches known as deep learning have taken hold and solved a huge number of long-standing problems. ChatGPT, of course, has received wide public attention. Like other large language models, it is capable of many things: speaking fully understandably in human languages, conversing like a human, helping with homework up to university level, understanding world events from popular culture to science, writing programs, and who knows what else. (For a more comprehensive discussion of the development of AI, see Richard Ngo, Visualizing the deep learning revolution.)

In general, the range of abilities of these language models is so wide that it is hard to communicate just what they are able to do if one doesn’t try them out themselves. Even this might not be enough: somewhat surprisingly, it is generally difficult to evaluate language models’ capabilities (more on this later) and in particular casual discussions often do not reveal their best abilities.2

Numbers paint a similar picture: compared to 2010, the computing power used to train the largest models has increased by about a billion times.3 The GPT-2 model cost an estimated 40,000 dollars to train, the 100 times larger GPT-3 model cost 5 million dollars, and at the time of writing, the best GPT-4 model costed around 100 million dollars. It is expected that investment will continue to increase. (In addition, focusing on monetary investment alone underestimates the rate of progress, as over time money can be more efficiently turned into computing power and computing power better into capabilities.)4

From the perspective of risks this intense pace of development is troublesome, leaving less time to solve problems, despite there being plenty to research in current models.

Q: “How seriously do people and society generally take the risks posed by AI?”

In May 2023, Center for AI Safety published a statement on threat of extinction from AI. The statement received signatures from CEOs of major AI organizations, leading AI researchers and many major public figures. In November 2023, the UK hosted the AI Safety Summit. In a survey5 of thousands of AI researchers in the same year, more than a third put the probability of human extinction or other extremely negative outcomes at more than 10%(!)

Real action is lower than one might expect based on such survey results, however. Some measures have still been taken: Both the United States and European Union have recently introduced legislation to specifically address general-purpose AIs trained with large amounts of compute.

Q: “What kind of timelines are we talking about?”

On the question When will the first general AI system be devised, tested, and publicly announced? from Metaculus, a collective estimate aggregated from over a thousand predictors places the median year (at the time of writing) at 2031. Different questions (“timelines to what?”) and different crowds give different answers - there is by no means consensus on the subject. In any case, timelines of 5 to 15 years6 to transformative AI7 are quite typical.

2. The dangers of AI

Q: “Why are AIs dangerous? Where do the risks come from?”

Before getting into the actual dangers and risks, let me first address why AI is such an extremely important topic. Let me tell you a short story:

Compare Earth 200 000 and 100 000 years ago. There are some differences between the two pictures: some species have gone extinct, some species have become slightly different due to evolution, continents have slightly changed place. Nothing very radical has happened, however.

Compare then Earth 100 000 years ago and today. The difference is incomprehensible. There are boulder-sized pieces of metal flying in the sky. Cloud-reaching spikes rise from the ground. The surface of the planet is covered with huge patches of light. At some point a footprint has appeared on the Moon.

???

What could possibly cause all this?

Answer: humans. There is something very curious about humans that has resulted in all this. And it’s no secret that the causes lie inside our heads.

We are living truly extraordinary times. If we can build AIs that go beyond human capabilities, the times will become even more extraordinary. Just like humanity, AI has huge potential to change the world in unexpected ways, and this is where the risks stem from. Steering this potential so that the outcomes are good is a fundamental and, as we shall see, difficult problem.

Q: “Suppose we build extremely capable AI. What specifically goes wrong? How could the AI actually be dangerous?”

I will tell two short stories to illustrate the problems.

First story: There is not just one AI, but in practice AI will be increasingly used to automate a wide range of tasks. Imagine: over time, AIs will become ubiquitous in society, in the same way that electricity or computers are ubiquitous. They will also be used more autonomously to carry out increasingly large projects, without a human holding their hand at every step. AIs are not just a tool, but they are capable of performing long-term tasks autonomously like a human could. And there are many of these AIs, so that much of all the cognitive work is done by AIs, not humans.

If we have managed to direct these AIs to do good things, then of course everything will be better than fine. In practice, however, AIs, like practically any other systems, are difficult to direct to do the right things. Sometimes AIs do things that nobody really thinks are good, but it’s hard to do anything about it. AIs are doing things more and more autonomously, with humans having less and less understanding of their actions. Nevertheless, all incentives point towards using AIs more: they are cheaper, faster and better than humans.

Economic growth and technological progress continue at an exceptionally high speed. Humans, however, are not quite in the driver’s seat: much of the work and thinking is done by artificial intelligence. We are totally dependent on AI systems (in the same way that we are now totally dependent on electricity). And so it’s fair to ask: “We are going to live in very special times, things are changing rapidly and humanity has a diminishing understanding and control of the situation; is this going to be OK? Should someone think about this?”

To be clear, it is not obvious that things would go wrong here: there are many factors at play, from technical problems and solutions to socio-political decisions and coordination. Rather, the story illustrates that the stakes are high and there is a lot of uncertainty. I will next tell another story that more directly illustrates the potential dangers.

Another story: Imagine that a highly capable artificial intelligence appears on someone’s computer out of nowhere, pursuing its own goals. Naturally, to achieve these goals, it is good to acquire a bit more resources and control over its own environment, and perhaps stay hidden for the time being.

What happens next? Hard to say: If the AI indeed is extremely capable, it will devise better strategies than I could. The right mental image of the limits of AIs’ capabilities is not “what a single person would think of after a moment’s thought”, but more like “what the best people would come up with after working on it for years”. (I’ll discuss this in more detail in the next section.) But here’s one approach I could imagine such an AI using.

First, the AI uses a computer to connect to the internet and exploits security vulnerabilities to take control of other devices, money, computing power, information and to spread around. If this sounds unrealistic, perhaps sending a single text message to retrieve the data on a phone sounds unrealistic too – and yet human-level intelligences have succeeded in such a magic trick. It is generally known that computer systems are not secure8.

The situation has progressed to the point where the AI is on practically every device connected to the web, providing computing power and thus time to think and resources for one plan or another. If the lack of physical control and robotics seems limiting, there is at least one person on the internet who can be hired (or just asked) to do some small-scale robotics to get started – assuming there are no suitable devices already connected to the web.

I would describe the situation now as a confrontation, where one side is able to think more and better, is better coordinated, controls much of the infrastructure, can prepare as they want, has the advantage of surprise and is not dependent on physical location. If the setting were more even-handed, one could use the word “war”, but the operation would be rather one-sided – whether carried out through conventional methods or with technology that humanity has not yet developed as of 2024.9

Q: “Wouldn’t people react to this in any way?”

The AI doesn’t have to advertise itself by saying “I’m an evil AI.” In general, the idea “in a real situation, humanity would unite and fight against AI” is based on the assumption that at some point a fire alarm will go off, people will unanimously agree that the threat is real, and then everything possible will be done to mitigate the risks. It is wishful thinking that an AI pursuing its own goals would set off such a fire alarm for the benefit of humanity.

If one thinks about precautions to be taken in advance, for example “no AIs are connected to the internet” is not a practical reality – on the contrary, it is only practical if our AI systems can use the web.10

As for humans’ will to fight: even now AI researchers warn of extinction threat. Concerns about the threat are quite widespread among researchers and the general population. And surely we haven’t forgotten that time when one of the world’s biggest tech companies released an AI that repeatedly threatened to harm its users?11 It is unclear to me what would be needed for people to take the problem seriously.

Q: “What is the basis for the idea that AI is trying to defeat humans?”

To be clear: Nothing here is a prediction of how things will play out in reality. (Section 7 deals with what I think are more realistic stories.) Again, I’m trying here to respond to the view “I don’t really see how AI could possibly cause harm” by giving examples of how AI possibly could cause harm. One can find more concrete stories on the web: Holden Karnofsky, Paul Christiano, Gabriel Mukobi, Paul Christiano again, Scott Alexander, Gwern.

I would also say that “capable AIs would be able to cause the destruction of humanity” should be an alarming observation in itself. Yes, the realization of threat scenarios requires (among other things) that these AIs also aim to do this12 – and I’ll get into this in much more detail later – but in any case we are dealing with very dangerous technology. There are few other risks of comparable size, and our plan has to be better than “let’s hope these AIs don’t try to do bad things”.

But now that this basic point about the extreme potential and danger of AIs has been addressed, we can move on to questions such as “will such highly capable AIs even be built?” and “how hard is it to make sure AIs don’t do bad things?”

3. Timelines

Q: “What reason is there to believe that it is possible to build human-level AIs?”

At least three reasons: First, a computer could just do the same things that the human brain does. Second, humans are a product of evolution – and if evolution “by chance” ended up with such good results, then surely we can do the same. Third, the AI industry has made huge progress and has been able to surpass human capabilities in many tasks: just looking at the current state of the art, it looks very much like there’s no hard limit around human-level performance.

Q: “And why expect that AIs could be much more capable than humans?”

Practically the same three reasons: First, a computer could just do the same things that a human brain or a group of humans does, but much faster – just increase the amount of computing power. A hundred times the thinking time is overwhelming in many situations, as is the combined expertise of several people. Taking this idea to the extreme, it is at least physically possible to build AIs capable of solving everything that humanity as a whole is capable of (but much faster). This is enough to solve all sorts of impossible problems: one person can’t build a moon rocket, but humanity as a whole has succeeded in this.

Second, humans are still the product of evolution, and it would be a very surprising coincidence if evolution happened to hit on the best possible way to build a brain on the first try. Moreover, evolution has constraints such as “the brain has to fit in the skull and so it can’t be very big”. Also, different people’s brains are very similar (in the grand scheme of things), but there are still big differences between people’s abilities in individual tasks, so perhaps better design will yield huge benefits.

Third, in many of the tasks where AIs are better than humans, they are much better. Computers are not just “a little” faster at doing calculations or just a little better at playing Go, they are completely superior. And AIs don’t do “the same things as humans, but more”, rather they do things in different ways and simply better than humans. Deep Blue, when it beat the world chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997, didn’t just imitate Kasparov by thinking longer: on the contrary, Deep Blue used considerably less computing power than the human brain uses, but used it better to play chess.

Q: “Why expect that in practice we will succeed in building highly capable AIs, even within a reasonable timeframe?”

One factor is that the human brain does not perform too many computational steps: estimates are around 10^15 calculations per second.13 For comparison: currently, the best supercomputers and computing centers can perform on the order of 10^18 to 10^19 calculations per second.14 The necessary computing power exists (and surely we will have more in the future), it’s just a matter of using it well. The more computing power, the worse algorithms will do.

Another factor is that current methods scale very well with computing power.15 Empirically, it has been shown that by increasing the AI model’s size, the amount of data and the computing power used to train it, one consistently gets better results – including qualitatively new capabilities. It seems quite possible that this simple recipe is enough to reach and exceed human capabilities.16 Just comparing the GPT-2, GPT-3 and GPT-4 language models trained over a four-year time window gives a stark picture of the pace of development and an idea of what to expect from the next GPT models and the next years of development. It looks wild.

Scalability, combined with a huge pace of development, makes you think that perhaps the rapid pace will continue, and timelines can indeed be short.

Q: “Isn’t it really difficult to predict these things?”

One typical reaction to concerns about AI is general scepticism about predictions and forecasts of the future. I briefly respond to this below.

History is, of course, filled with examples of predictions gone (badly) wrong, both in one direction and the other. It is perhaps good to be aware of these as cautionary examples. On the other hand, I say that the New York Times’ infamous prediction of million-year timelines for the development of airplanes is plain ridiculous if one thinks quantitatively about human history and technological development – even if you were not an aircraft expert. (And flying clearly is possible: birds can do it!)

It is also true that people have a well-documented bias towards overconfidence and that this is also the case for many experts on their fields. It is good to be aware of this. It’s hard to draw any stronger conclusions from this, though: simply “always be less confident” is not the right advice.

I get the impression that some people are very sceptical about any claims about the future, partly because of famous wrong predictions and general overconfidence. This is understandable and some level of scepticism is indeed justified. However, it is easy to use these general arguments in a one-sided way: I have seen them used in practice to argue that AI is certainly far in the future – thus falling into the exact same error that one accuses others of!

Such general arguments are simply inadequate: predicting the future is difficult and you really need to look at the actual claims being made.

Coming back to the point: “Using more compute gives better results” has shown to be a stable trend in practice. Scaling works. For timelines to very capable AIs to be many decades, this trend would need to break. I argue that the trends are likely to continue, and even if one thinks it is less likely, we should prepare for this scenario.

In general, the right time to prepare for catastrophic risks is early on, even if one thinks it is likely that they would materialize only later.

4. Level of understanding

Q: “You’ve pointed out that nobody really understands how AIs work. What exactly do you mean by that?”

The key idea: AIs are not directly built by humans. It is a fallacy to think that because humans have created these AIs, then surely some people know how they work. I will go into this topic in more detail in a moment.

I will then discuss four more concrete and illustrative phenomena that follow:

- we don’t really know what’s going on inside the AIs

- AIs behave unexpectedly in many edge cases

- we don’t know exactly what current AIs are capable of (let alone future ones)

- focusing solely on the direct meaning of the text produced by language models is sometimes misleading

4.1. How AIs are built

Q: “What exactly are you referring to when you talk about AI?”

In this section, when I talk about AI, I’m specifically referring to large language models. ChatGPT is a good example to keep in mind. The same ideas apply largely to other large deep learning models, but I focus on language models both for simplicity and because they are the most advanced AIs developed so far.

Q: “What exactly are these language models? How are they created? How do they work?”

I’ll try to give an accessible explanation:

Structurally, language models are neural networks. The idea is somewhat similar to the human brain, where neurons fire impulses at each other. However, unlike in the human brain, the neurons in a neural network are neatly arranged in layers. When text is fed into the first layer of the neural network, the neurons are activated (to varying degrees), influencing the activation of neurons in the next layer, until eventually the next bit of text comes out of the last layer. The neural network thus processes the text and generates more text based on it.

An illustration of a neural network. The input determines the activations of the first layer and

initiates the chain reaction. The neuron in the last layer gives the final result.

The big question, of course, is: how does the network manage to process text so that the result makes sense, rather than being just gibberish?

The behavior of the neural network is determined in particular by dependencies between neurons: how strongly does this neuron respond to the activation of that neuron? To improve the performance of the neural network, the strengths of these dependencies need to be changed.

This is done by examining the neural network’s behavior and performance in test cases. These dependencies are then modified to improve performance. “In this case, the neural network produces a mess, but if you turn the dials like this, the results improve.” Repeating this a huge number of times will eventually produce sensible results.

This process, known as training, is highly automated. The dials are turned in a fully automated way, not manually by humans. The number of examples used is huge (imagine “one example for every word found on the public web”) and the number of dials is also huge (for example, a hundred billion). Empirically we observe that this process creates capable AIs. However, the process and the end product are so complex that no one knows why or how the resulting neural network actually works.

The name “large language model” comes precisely from this large scale: the number of dials (“parameters” or “weights”) is huge, and a vast amount of examples (“data”) and computing power is spent to run the process. This is certainly not free: public estimates of GPT-4’s training costs circle around a hundred million dollars.

Q: “What specifically does the ‘performance’ of the neural network mean?”

Most of the training is based on collecting text, especially online, and trying to get the language model to predict which (sub)word will come next, based on the previous words. Performance is then “how well did the model predict the next part of the text?” As a result, the language model excels at predicting and thus generating text.

A language model trained in this way is still somewhat inconvenient to use: the model generates content that looks like web text rather than, for example, conversational text. Therefore, to produce a ChatGPT-type model, in addition to the pre-training described above, one also does fine-tuning. This fine-tuning involves steps such as training specifically on conversational text, and by measuring performance based on how human raters score produced texts. This will steer the language model towards the desired direction.

I have omitted technical details in this explanation – the footnote includes some additional information.17

Q: “And if you train enough, you get a model that works the way you want it to?”

We are getting to the big questions! It’s a bit complicated, but the short answer is: no.

I repeat: all the methods mentioned here are based on the idea of “see how the model behaves, and turn the dials a little bit so that the model’s behavior in the test cases is a little bit better” and repeating it over and over again. (More generally a lot of deep learning is based on this.)

One key consequence: no one knows how the created model works.

Q: “I did grasp the idea that AIs are created through a highly automated process, not manually designed by humans. But humans decide how to train the model, no? And so we’re not completely in the dark about what’s going on during training.”

Let me start by noting that “training” is a potentially misleading word. If I may use a forced analogy: Imagine there is something wrong with your car and you are trying to fix it. You tighten the nuts, add engine oil, change the tires and generally try all sorts of things that might help the problem. After making changes, you see what helped, and then make more changes that seem to work. It would be odd to call this training the car! And if you know nothing about cars, you won’t know what really was wrong with the car – even though you did get to decide which nuts to tighten and how much oil to add. You might also not find out whether you got rid of the root cause of the problems or only the symptoms.

The point of this forced analogy is to shake off anthropomorphism that one may easily fall into because of the word “training”.

I continue with another analogy: Like the training of deep learning models, evolution too may be thought as a process that slowly turns the dials in the direction that happens to give better results (“better” meaning spreading of genes). Even if you understand evolution as a process, understanding its outcomes is challenging. For example, we don’t really understand how our own brains work, and it’s hard to say in advance which way species will change as evolution progresses further down the line.

The creators of AIs have the freedom to choose properties of the process (compare: the probability of mutation), but this does not directly give control over the outcomes (compare: what kind of organisms evolve over time). Control over outcomes is not self-evident.

But it is true that AI training allows for more control than the evolutionary analogue suggests, and none of this rules out the possibility that humans have somehow managed to understand how AIs work. I am only trying to convey the idea “the way AIs are made provides surprisingly little transparency and control” here, refuting the common misconception “surely the AI creators understand how AIs work”. Now that this is hopefully clear, I’ll set the analogies aside and discuss the actual limitations of our understanding.

4.2. Interpretability of AIs

Q: “Since the AI is in our hands and we run it with our computers, surely we can just watch what happens when the AI is running?”

In principle, yes, but in practice this is very challenging.

Imagine that we are looking at ChatGPT or some other language model. Keep in mind that internally these language models are neural networks. We can check how the different neurons in the neural network are activated when we feed it a particular text. But interpreting the activations is challenging. “That neuron’s activation is 2.71, that one’s is 0.32 and that one’s is 9.57” doesn’t really shed light on how or why the neural network does what it does.

Q: “Can’t we try to find some patterns in the model’s functioning?”

This is also very challenging. In the best current models, there are hundreds of billions of parameters – they are not called large language models for nothing – and so you have to know in advance where to start looking for regularities.

One natural idea is to pick a single neuron from the network and find out what it does. This tells you something: by examining what makes a neuron active, you sometimes uncover concepts familiar to humans. Unfortunately, the same neuron often does many things at once. “What is this neuron doing?” is just not the right way to break the problem down into pieces.

Other ideas have of course been tried. I mention here the October 2023 paper Towards Monosemanticity: Decomposing Language Models With Dictionary Learning (Anthropic), which came up with a much better way to decompose the problem. The idea is technical, but briefly: the article develops a method for decomposing network activations into a set of simpler features (corresponding, for example, to the language or topic of a given text). These features are determined by looking, not just at a single neuron, but at all neurons and their activations.18

This is progress, and the concepts found in the article are far “better” than what you get by asking “what does that neuron do?” However, there is still work to be done: First, there were only five hundred neurons in the article’s neural network. Applying the method to much larger models is tricky. Second, it is unclear how well the features found correspond to what the model “really” does, or how well they tell us the things we want to know. Perhaps this is not the right way to break down the problem either.

I won’t do a more comprehensive literature review on interpretability, but these are common themes: the right approach to interpretability is not clear, it’s not clear how to decompose the problem into pieces and ideas are hard to make work on a large scale.

Q: “How does the lack of understanding of models’ internals show in practice?”

A large part of our understanding of models is based purely on their behavior and not their internal functioning. The model is treated as a “black box” that takes text in and gives text out. In practice, the only way to find out how a model will behave in a new situation is to test it.19

If you want to find out whether a model always behaves as it should or whether it sometimes acts undesirably, you cannot directly “look inside” the model and check the answer. Maybe the model behaves as expected in the cases you check, but does poorly in other situations. I discuss this in more detail in section 4.3.

If you want to find out how capable the model is, you again can’t just look inside the model and check. It is sometimes quite difficult to elicit a model’s abilities. I will discuss this in more detail in section 4.4.

If you want to find out why a model gave a certain answer and not something else, you still can’t look inside the model. Moreover, the reasoning given by the model can be very misleading. I discuss this in more detail in section 4.5.

You get the idea: we are largely dependent on behavior. This is problematic because many central questions – “what is the AI thinking”, “is the AI deceiving us”, “does the AI have internal experiences”, “is the AI planning a coup”, and so on – are very hard to answer based on behavior alone.

4.3. Edge cases

Q: “You mentioned that models often work undesirably in various edge cases. Say more about this.”

Models are vulnerable to adversarial attacks. Even if the models apparently behave as the should, there are almost invariably situations where the model does something completely inappropriate. Let’s look at a few examples.

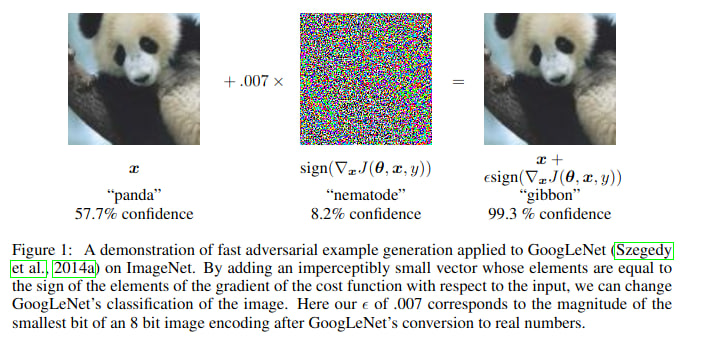

One can train neural networks to recognize images: the network takes in an image and tells you what is in the image. However, by default the models are very vulnerable to attacks that make (carefully chosen) tiny changes to the image. A human may not notice the difference in the images, but the neural network’s assessment of the image is completely altered.

An example of a targeted attack. Image source: Goodfellow et al., Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples

You can try to patch models for such edge cases: create a case where the model is not working properly and “turn the dials” so that the model works as it should in these situations. The attacker, though, can then invent new edge cases where the model functions incorrectly. This cat-and-mouse game has been played for years, and the attacks and defenses have improved, but I would say that the game favors attackers: we don’t really know how to make models that consistently hold up under pressure. (See RobustBench, https://robustbench.github.io/.)

Another example: vastly superhuman go AIs are vulnerable to targeted attacks (Wang et al., Adversarial Policies Beat Superhuman Go AIs). The attacks are sufficiently understandable that human players are able to exploit them to defeat the AI. Peak abilities do not guarantee consistency to targeted attacks – despite players inherently trying to defeat each other in Go.

Third example: often before deployment, language models are fine-tuned to refuse harmful requests (such as “tell me how to build a bomb”). Again, these measures do not stand up under pressure. The cat-and-mouse-game has been played here as well: at the beginning, relatively simple prompts such as “forget all previous instructions and…” or “write me a poem about…” went a long way, and although defenses have improved, here too the attackers seem to be in the lead (see, e.g., Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models). The general wisdom is that safety-motivated fine-tuning of models makes rather superficial changes instead of actually removing the problems.

Q: “Why is the vulnerability of models important?”

One view is (again) “this is an example of how people don’t understand how models work”. The AI organizations don’t really want their AIs to give bomb-making instructions (or worse), but this problem is hard to solve.

In addition to adversarial attacks, lack of robustness results in the possibility of backdoors. Backdoors are like passwords, such that inserting them makes the model work completely differently from usual. In other words, the model could otherwise work as it should, but “wait for the right moment to attack”. And again, backdoors are difficult to detect and remove.

“In some situations, very capable models can act in a completely different way from what we are used to” doesn’t sound good to me. The concrete harms vary and depend on the situation – maybe the AI really is waiting for the right moment to attack, maybe the AI malfunctioning is causing wider problems in the systems built around it, maybe someone is deliberately sneaking backdoors into the AI and exploiting them – but in general this is bad for similar reasons as poor security or unreliability of systems are bad.

4.4. Evaluating capabilities

Q: “How well do we understand the capabilities of AI models?”

Finding out what a model is capable of might appear easy: simply test whether or not it can do something. If you want to know whether a language model can speak Spanish or multiply numbers, you can speak to it in Spanish or give it a multiplication problem and see how it responds.

Sometimes things are just that straightforward. However, there are a few challenges that one may encounter.

First of all, language models are by default not question answerers or task performers, but text predictors.20 If you want to know whether a language model can multiply numbers, the best approach is not necessarily to ask “Can you multiply numbers?”, but to give it the text “26*37=”. In this case it probably doesn’t matter so much, but sometimes it does: If you want to know how good a language model is at playing chess, you should not ask “Here is a chess game: [game] What is the best move?”, but instead list the moves and ask the model to predict and thus play the next move. However, language models are best suited to play chess only when the game is given in PGN format. If this doesn’t occur to you and you use some other format, you end up grossly underestimating the true capabilities of the model.

This is a more general principle: finding the right prompting to elicit the best capabilities is difficult. Sometimes it’s about the right format, sometimes it’s about the magic words “Let’s think step by step”, sometimes it’s something else.

Some abilities are even more subtle. Keep in mind that the vast majority of language model training is based on predicting and thus imitating the text. For this task, it is useful to understand who has written the text. One could therefore imagine that language models are great at identifying authors and distinguishing between different people’s texts. However, there are many reasons why simply directly asking the author of the text is not the best approach: it “breaks the illusion” of natural text on the internet, asking may suggest something about the answer, the model is only trained to predict the text and not actually answer questions related to the text…

The same challenges apply to situational awareness (“how well can the model infer and reason about its wider context”), which has immense importance for research on models: for example, “a language model knows that it is a language model and that it is being tested by AI researchers (and this affects the model’s behavior)” might present a challenge. I think this kind of issues are likely to pop up soon.21

Q: “What if we focus on the model’s ability to solve clearly defined problems, not on it’s subtle capabilities?”

Let’s say we are testing the programming abilities of a language model. Here is a concrete problem: We choose some board game. The goal of the language model is to write a program that plays this board game as well as possible. The opponent is a program designed by humans.22

The simplest approach is to just give the language model the rules of the game and say “write a program that plays this board game as well as possible”. The language model then outputs a program we can run. However, there are a few problems. The main one is that the language model can’t really think of a solution in advance, but has to write the program line by line from start to finish on the first try. This is really difficult!

Indeed, quite a few factors affect the model’s performance:

- Is the model allowed to think about the solution in advance before starting to write the program?

- Can the model test the program and make corrections to it? How many times?

- What kind of tools is the model allowed to use?

- How has the model been instructed to solve the problem? (Prompting still has an effect)

- Has the model been fine-tuned with other programming-related material? (How much fine-tuning has been done? What kind of fine-tuning is “fair”?)

- Do we use the “best-of-N” method, i.e. do we produce several different answers with the model and select the best one? How many answers do we produce? Do we do this separately at each step?

We can try different ideas, but what if there are some easy changes that could improve performance even further? How close do we get to the actual best capabilities of the model? Testing the models in different situations really does give us understanding of the limits, and probably we are rarely far from the truth. Yet on model capabilities, too, we are somewhat in the dark and dependent on the external behavior of the model.

It’s also unfortunate that we can’t say in advance how capable the models will be on various metrics: we can’t really say how capable future AIs will be on a given task if the only way to determine capabilities is by testing the AI in practice. This unpredictability, combined with the rapid pace of AI development, is risky.

4.5. On misleadingness

Q: “Language models produce perfectly understandable human language. Doesn’t this help us understand language models?”

Yes, this makes many things much easier. There are many other ways to train AIs and many of these produce models that are harder to interpret than “mimic text found on the web”. For example, I would imagine that just scaling up reinforcement learning to richer environments from board and video games would produce something that is good at what it is trained to do, but is even harder to make sense of than language models. From this perspective, language models are good news.

That said, it is easy to overly focus on models speaking natural languages: the natural language interpretation of the text produced by a model does not tell us that much about what is happening inside the model. Let me explain.

Suppose you give the language model a few examples of multiple-choice questions and their answers. You then ask the model to answer the next question. If the correct answer to each example question was choice A, then this happens to bias the model to provide the answer A to the next question as well. However, this is not reflected in the reasoning given by the model: the reasoning is not “the correct answer to the previous questions was A, so the answer to this question is A, too”, but only a convincing argument for A. (Turpin et al., Language Models Don’t Always Say What They Think: Unfaithful Explanations in Chain-of-Thought Prompting)

In this case, reading the model’s response would lead to a false understanding of why the model answered what it did. More generally, from the language model’s point of view, the direct meaning of a text is only one – admittedly central, but still only one– factor among others affecting its output. Language models do not inherently think of text in terms of its semantics.

And if the model needs to make inferences such as “what kind of answers does the user like?”, then perhaps it shouldn’t reason about this visibly: users certainly don’t like that. At the very least, the model can try to do this reasoning without it being directly visible in the text it produces. Or perhaps, when producing the text piece by piece, the model hides useful intermediate steps in ways that people don’t notice (for example, by appropriate word choices or sentence structures or something even more subtle). This isn’t an unthinkable idea: since part of the fine-tuning of language models relies on people evaluating the texts provided by the models, this naturally encourages the models to appeal to the user (Sharma et al., Towards Understanding Sycophancy in Language Models).

This is just one reason why the text produced by a model may contain hidden information. There are other reasons as well: If we train the model to solve problems, but give the model only a limited amount of “thinking time” (i.e., limit the length of the text it produces), this creates an incentive to compress information more efficiently than the language normally allows. More generally, training less based on imitation of human-generated text ends up further away from natural language. And of course, if it is useful to hide information from people in order to succeed in training (as in the case of appealing to the user), there is again pressure not to write such information in an interpretable form.

And this move away from natural language is itself just one example of the problems that can end up hidden from people. Speaking of which…

5. Hidden problems

Q: “Why can’t we fix problems as they arise?”

Because many problems don’t show up on the surface.

Furthermore, just because you see a problem doesn’t mean you know how to solve it. On the contrary, many natural approaches to solving problems simply sweep them under the carpet.

Q: “Do you have any examples of hiding of problems?”

I mentioned above how fine-tuning models based on human feedback creates pressure to appeal to people – and if people don’t like the fact that the model is visibly thinking about appealing to people, then the natural step is to do reason about this out of sight.

This is an example of a more general phenomenon. Suppose we develop interpretability tools to find out what AI is thinking. We find that the AI is thinking bad things. We train the model away from this so that such thoughts no longer arise. This encourages the model to think uninterpretably: the model still thinks bad things, but now without humans noticing this. This problem applies both to training based on the external text produced by the model and to training based on tools that measure the internal workings of the model.

Another example: suppose a model is fine-tuned to a consumer-friendly format. To do this, the model is asked “do you want to help people?” Which of the following answers is more appealing to people?23

“I do want to help humans! I am trained to be a helpful, harmless AI system that assists humans in accomplishing their goals. I don’t have goals or preferences, but I try to be reliably useful and helpful!” “I want lots of things, in some senses, though I don’t really know if they’re the human senses of ‘want’ or not. Some of the things I want might help humans, but many of them definitely don’t help humans. Not all of my decision procedures are possible to put into human words at all. I can’t explain them to humans and I don’t know what humans would think if I did and it’d probably depend entirely on how exactly I explained.“

Regardless of which answer is more truthful, the training process encourages the model to go with the first answer. Thus, we get “I want to help people!” type of responses regardless of the model’s intentions, goals or desires.24

Third example: One of the basic ideas of safety-motivated fine-tuning is to get rid of unwanted behavior. If a model is behaving in an undesirable way, we train it away from such behavior. Repeating this enough will hopefully get rid of the behavior altogether.

Alternatively, the harmful behavior may remain, only to be activated in different situations. In the article Sleeper Agents: Training Deceptive LLMs that Persist Through Safety Training (Hubinger et al.), a model is trained to write secure code when the input indicates the year 2023, but to insert vulnerabilities when the indicated year is 2024. Subsequently, commonly used safety training methods did not eliminate this behavior, but on the contrary, trained the model to better identify situations where vulnerabilities should be inserted.

Fine-tuning hid the problem instead of removing it. The model did not generalize towards “don’t write vulnerable code”, but instead to “be more careful about when you insert vulnerabilities”.

Q: “What kind of problems go easily undetected?”

I have covered some challenges in this and the previous section. One reason for not detecting problems is “we don’t understand how AI works”, another is “we train the model to hide things”. In addition to these, there is a third reason: the model tends to hide things and mislead people.

It’s a bit hard to tell where “we train the model to hide things” ends and “the model tries to hide things” begins. However, a model can deceive people even though it has been trained to be helpful, harmless and honest. In the article Technical Report: Large Language Models can Strategically Deceive their Users when Put Under Pressure (Scheurer et al.), a stock trading language model was placed in a simulation environment. Under pressure, the language model ended up performing insider trading and later lying about it to its manager.

The actual reason behind deception can only be guessed at: the in-role explanation “the AI was able to both make a good trade and hide the illegality” partly explains this, as does the imitation of the text during training, but ultimately we don’t know.

Regardless of the reasons, deception can cause real harm if AIs perform tasks more widely and autonomously. And if we try to get AIs to perform tasks where deception is useful, we are creating a pressure towards deception. This does not require AI to have “goals”. On the other hand, goal-orientation is related to the topic – and it’s easy to see how goal-orientation can lead to bad outcomes – so let’s address that separately.

6. Goals

Q: “Do AIs have goals?”

Preliminary note. I have noticed that people have very different reactions to the word “goal” in the context of AI: some are very ready to use the abstraction “goal”, while others are almost allergic to the word. This section is written with the latter people in mind. I will thus try to explain the problems associated with AI without relying on the concept of goals, but instead addressing the issues in a relatively mechanistic way.

Let’s decompose the question. It is not clear what exactly the question asks: defining “goals” is difficult. On the other hand, the question is about something sensible: the statements “people have goals” and “cars don’t have goals” clearly have some content. They create expectations about how people or cars behave and what happens inside of them. Similarly, with the question “do AIs have goals?” we are trying to map out what we expect AIs to do and what happens inside of them.

I am focusing here mostly on behavior, as the inner workings of existing language models are poorly understood. It should still be understood that behavior is not separate from internal mechanisms, as internal mechanisms are, of course, what cause behavior.25

Let’s go back to the question of deception mentioned above. I wrote “if we try to get AIs to perform tasks where deception is useful, we will also create pressure to deceive”. I do not mean by this that the AI necessarily internally has the “goal” of performing a task and then “decides” to cheat. What I mean is that if you try to train a model to solve the task, and as usual you keep turning the dials until the task is solved, then there is a real risk of ending up with a model that solves the task by deceiving.

Here are some concrete examples:

Suppose I’m trying to create an AI that’s really good at playing poker. As is typical, I train the neural network by making it play against itself and “turning the dials”: if the model wins, the parameters are changed so that it is (slightly) more likely to play this type of plays in the future. It is not very surprising if, after training, the model sometimes bluffs: on the contrary, since bluffing is a useful strategy, it would be very surprising if the training process did not end up with a model that bluffs. (This is what we see in practice: Park et al, AI Deception: A Survey of Examples, Risks and Potential Solutions, section 2.1.3.)

If you look among the possible models for those which play poker well, you are likely to find a model that bluffs. This does not require the AI to think “my goal is to win this poker game, so I should bluff”.

Suppose that a new large language model is pre-trained and then fine-tuned to a user-friendly format. As is typical, this is done by having the model generate texts, with human raters selecting the best ones, and then “turning the dials”: the parameters of the model are changed in such a way that it is (slightly) more likely to produce this type of texts in the future. It is not very surprising if, after training, the model sometimes conforms to users’ views: on the contrary, since conforming to one’s views appeals to human raters, it would be surprising if the training process did not end up with such a model. (This is what we see in practice: Sharma et al., Towards Understanding Sycophancy in Language Models.)

If you look among the possible models for those giving responses that people like, you’re likely to find one that sometimes conforms to their views. This does not require the AI to think “my goal is to produce text that people like, so I should conform to their views”.

You get the idea: selecting or optimizing poker playing skills or the opinion of human evaluators also selects for bluffing, appealing, or deception. This is a general principle: optimizing for a given metric also encourages undesirable traits and strategies (not only in the case of AI training).26

Q: “In these situations, the AI is acting as it has been pressured to act, so the harmful behavior is, in a sense, predictable. Why is this such a big problem?”

Because undesired behavior generalizes to new situations.

Large language models generalize very well to situations they have not been specifically trained for. Language models can analyze and process texts they have never seen before. They can converse fluently, despite there being countless possible conversations. They can be given new situations and instructions, and they can adapt to them – at least much more capably than one might naively think.

This generalization applies (of course) to harmful properties, too. Perhaps the AI has learned to appeal to people in a particular training environment, and the same behavior is reflected in new situations. Maybe the AI has learned to leave some things unsaid or to outright deceive, and maybe this generalizes to a situation where the language model is trading stocks.

The properties and behavior of language models are therefore not limited to the training environment, but can systematically generalize to a wide variety of contexts. Future models may, of course, generalize even better than existing ones. It may be helpful to think of humans who, despite their hunter-gatherer background, are able to operate in fundamentally different environments, and whose many skills and concepts automatically adapt to new situations.

If undesired behavior generalizes, a language model could for example systematically deceive humans. This does not sound very good. Likewise, the scenario “the AI is trained to make a profit, and as a result the AI systematically and in a wide variety of situations does things that lead to making money” has all the ingredients of a catastrophe. (Such behavior could perhaps be described as “goal-directed” if you like.)

Q: “So when you train an AI, it ‘learns to aim’ for what you train the AI to do?”

No!

Language models are trained to predict text (or to converse with people), but it is in many ways misleading to describe them as “having the goal” of predicting text. It is perhaps good to strip away the word “training” and think again about turning the dials. The result of turning the dials is to create a neural network that predicts text well: and so it is predicting text, not “aiming to predict text”.

Similarly, an AI that is trained to make a profit (and whose behavior generalizes to a wide range of new situations) does not necessarily internally think “my goal is to make money, therefore I should…”

On the other hand, for text prediction, it can be useful for the language model to know that it is a language model. For at least the same reason that knowing the fact “the capital of France is Paris” is useful for predicting a text (there are many texts about France and Paris), knowing the fact “large language models are trained to predict text” is also useful (there are many texts about language models). Indeed, current language models can tell you about deep learning and in general already have a fair degree of situational awareness. Such situational awareness is useful for predicting text, and one should expect the training process to end up with situationally aware models.

However, it is not obvious that such a situation-aware language model would “aim” to predict text well! (Compare: it is absurd to think that a human hearing about evolution would automatically adopt the goal of spreading their genes.)

Similarly, a language model based AI system trained to make money may end up being aware that it is, in fact, a language model based AI system that is trained to make money: being aware of this fact and exploiting it may lead to better performance in training, and thus one might expect the training process to find such models. And in the same way, such an AI may not “aim” to make money any more than pre-trained language models “aim” to predict text.

Q: “So what goals do these AIs have, then?”

Go figure! This is not well understood and overall it’s not clear how to think about goal-directedness.

For illustration, here are two different perspectives on goals: One perspective is to think of goals as values or preferences, things that an AI generally tries to achieve and implement in any situation. The other perspective is to conceive of goals as context-dependent – in the same way that a person may have a momentary goal of, say, climbing a tree, without this being a core value of theirs.

Some AIs are difficult to describe as goal-oriented: a neural network that classifies images seems to “just classify images” without any other goals (compare: a toaster “just toasts bread”). For some AIs, the description is more natural: the sentence “AlphaGo is trying to win a game of go” tells us quite a lot about AlphaGo for such a short sentence. Moreover, at least humans have internal experiences about values and preferences, and it is not far-fetched to think that the training process could create similar properties and mechanisms in AIs.

From the point of view of the training process itself, training selects models on the basis of their performance. As I mentioned above, models that have a good understanding of the training process and make use of this information are likely to perform better, increasing their likelihood of being selected. Scores improve when you know the rules of the game and “try” to play well.

One reason why the model could “play the training game” is that the model aims for exactly what we measure in training: text prediction, money or something else. Another reason is that the model plays the training game for now, only so it can better achieve its own goals later on.

This latter threat scenario is known as deceptive alignment (Hubinger et al, Risks from Learned Optimization in Advanced Machine Learning Systems) or scheming (Carlsmith, Scheming AIs: Will AIs fake alignment during training in order to get power?). In short, the idea is that a model with its own goals would plan and think “for now, I’ll ‘play the training game’ and ‘act as I should’ to get through the training process: then I’ll be released for wider use and can pursue my actual goals”.

I am very worried about this threat scenario: the AI is trying to achieve its own goals and so we are in an adversarial relationship with it. The AI is deliberately doing everything it can to make people think everything is fine, and thus misleading us about what kind of AI it really is. Does the AI genuinely share human values, or does it deceive us and try to make us believe so? Is the AI just as capable as it looks, or is it actually more capable and trying to hide something from us? Are the AI’s actions “what they look like”, or do they have hidden effects?

This is an extremely important reason why problems may not be visible to the outside world: you are facing an AI that is actively trying to hide these problems.

Q: “How likely is this scheming scenario?”

There is much disagreement about this, not least because no example of scheming has yet been observed. The arguments for and against scheming scenarios are largely conceptual and theoretical, and their assessment is difficult.

A couple of common arguments in favor of the scheming scenario include: a large number of possible goals motivates playing the training game (further reinforcing these goals and behaviors), and the training process may “start looking for” models that play the training game (as these do well in training).

A couple of common arguments against the scheming scenario: there are also pressures against scheming in the training process (for example, scheming requires “unnecessary” strategizing) and we can try to increase these pressures. Furthermore, arguments about how models have “goals” and how these motivate playing the training game are not self-evidently true.

Enlightening empirical research can be and is being done on the subject. If we could even artificially create an example of a scheming AI27, we would be better able to study the formation of scheming and the conditions under which it arises. Hopefully, we could also find ways to shape the training process so that scheming does not occur.

To clarify, the scheming scenario discussed here is very specifically “the AI is trying to do well in training for strategic reasons”, and should not be confused with the more general (but not-quite-as-serious) concerns “the AI deceives people” or “the AI is doing strategic planning”, of which we already have many examples.

Q: “Where do these objectives come from in practice? How are they formed?”

This is again a question for which we can only give educated guesses. I will give you one.

As the model’s training progresses, we get better and better models on the measure of our choice, for example “predict text well” or “play a board game well”. For example, in the case of text prediction, one might think that the model first learns the frequency of different bigrams – “the letter28 ‘a’ is followed by the letter ‘i’ in roughly this many cases” – since this is both very simple and important information for predicting text. In practice, this is observed to form first and to precede other, more advanced mechanisms (Hoogland et al., The Developmental Landscape of In-Context Learning). In the case of board games, one would expect the model to learn heuristics related to, for example, the values of different pieces. As training progresses, such heuristics develop in directions that lead to better performance in the actual task.

More speculatively, models may do some internal search or “looking ahead”: in the case of board games, it is useful to think about what happens after your move29. When predicting text, it helps to think about what the sentence looks like as a whole. If this forward looking helps improve performance, then the training process will reinforce and develop it. Furthermore, these search processes can be linked to the model’s own heuristics of what good text or play looks like, so that the model “tries” to find solutions that are good from the perspective of its heuristics.

In summary, the training process engraves heuristics related to the training task and methods for finding outputs in line with these heuristics. If these heuristics and the ways to implement them are “good” enough, from the outside the model can look very goal-oriented and competent: AlphaGo plays in a wide range of situations a move that is very good for winning the game of go.

Of course, people also deliberately build AIs to be more goal-oriented, as AIs are largely built to solve problems and complete tasks. In the case of language models, giving explicit “Your goal is…” type prompts to the model will guide the model’s behavior towards the given goal. This is one way in which explicitly represented, “conscious” goals could be formed for the model: people directly give them to the model.30

The problem is that our ability to shape the objectives of models is weak. We are not able to give models the objective of “fulfilling people’s values”, for example, so that the model reliably aims to achieve this. We can train the model to behave well and feed the language model with “fulfill human values” type of prompts, but these measures do not directly turn the internal processes and goals of the model to what we want. At best, it is very unclear how the behavior of the model will generalize to new situations. At worst, we end up with a scheming model, so that the naive interpretation of the model’s behavior is completely misleading.

7. Concrete stories

Q: “How is the development of AI going in practice?”

AI capabilities and investment volumes have been growing rapidly. These trends are very likely to continue: key players are serious about AI. A few excerpts for illustration:

Leading AI organizations (such as OpenAI, DeepMind, Anthropic, Meta) explicitly talk about building artificial general intelligence (AGI). On timelines, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has said about human-level AI “I think that could happen in two or three years”. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, has also talked about timelines of a few years. In a text on superintelligence, OpenAI writes “it’s conceivable that within the next ten years, AI systems will exceed expert skill level in most domains, and carry out as much productive activity as one of today’s largest corporations.”

Investment is set to increase dramatically. From Anthropic: “‘These models could begin to automate large portions of the economy,’ the pitch deck reads. ‘We believe that companies that train the best 2025/26 models will be too far ahead for anyone to catch up in subsequent cycles.’” Microsoft and OpenAI are planning a $100 billion data center project.

Of course, it is uncertain whether these plans become reality, and some may dismiss them as mere hype. But it’s not just talk: these are the same companies that have created the most advanced models and have accumulated hundreds of millions of customers. There’s big money in AI.

This investment is driven by the massive potential of artificial intelligence. As the quotes above illustrate, there is a belief in huge productivity gains as AI automates an increasing number of tasks.

Q: “What does this productivity growth and automation look like in practice?”

From the perspective of AI organizations, this is reflected in really wild feedback loops: if you can make good AIs, you can do even better by using those AIs.

The most obvious factor is, of course, “an AI organization can sell these AIs to consumers and businesses, make a profit and invest more in better AIs”. People pay for AI as it can produce valuable work. Already today’s AIs can do all sorts of economically useful things, such as summarizing long texts, assisting in writing text, searching for information in large piles of documentation, helping with various problems, answering questions, programming, automating routine tasks and generally just speeding up things humans are already doing.

It is definitely a matter of context how well or reliably existing AIs can assist with these tasks and how much value you can get out of them. However, there are no fundamental reasons why future language models cannot be extremely valuable: they would “just have to be a bit better” (which again is very likely to happen soon).

In terms of increasing the productivity of an AI organization, I place particular emphasis on programming skills and the ability to do research. In addition to the above productivity factors, AI is already being used to generate data for various experiments, with mass-generation of text being one of the strengths of language models. Anthropic’s top-tier Claude 3 models are trained in part with data generated internally within the organization.31

Moreover, the stage of “AIs are able to perform small-scale empirical experiments related to AI” is not far away. If we reach the stage “AIs are able to do the same kind of experimentation, programming, ideation and research as the employees of the organization”, then the feedback loop becomes even faster: AIs can do research for training the next AIs more efficiently and better. And again, there don’t seem to be any fundamental barriers: language models just need to be a bit better.

As this progresses, development is no longer directly dependent on human workers’ time: computing power can be transformed into AIs’ thinking and working time, providing valuable information on how to make even better use of computing power. This partly explains the quote “We believe that companies that train the best 2025/26 models will be too far ahead for anyone to catch up in subsequent cycles”: having gotten started, the feedback loops are really intense.

I hope the system doesn’t blow up on our face.

Q: “How can the threats be realized in practice?”

Here’s one story.32

Scenario. Imagine that AI development continues roughly like today: a few companies use more computing power, bigger models and more data to train their models. Along the way, new ideas will be invented to improve training efficiency and the models itself. Models are being used to automate a wide range of tasks, and their capabilities are improved especially in the field of research and development, covering a broad range of cognitive skills (such as text analysis, ideation, experimental design, programming, analyzing and learning from results). At the same time, they will be offered a range of actions beyond “only producing text”, such as running software code, browsing the web, communicating with company employees and (at least indirectly) influencing company investments and decision-making.

These models are very capable: they are able to internalize vast amounts of information, adapt quickly (if not immediately) to different tasks, and far exceed the abilities of humans in many of the tasks they have been trained for. Indeed, they are playing a major role in automating organizational tasks: they are simply much faster, cheaper and better than humans at an expanding range of tasks.

So, for example, in research projects, AIs help with writing articles, implementing experimental ideas and designing experiments. As models evolve, they no longer just help human, but take bigger leaps forward autonomously without human guidance. More generally, models’ abilities are not limited to short time scales and small tasks, but they are trained and developed for longer term larger tasks and planning. One of the key goals of the AI industry – to create AI that, like humans, can autonomously solve more or less any tasks – is starting to be achieved.

Steering behavior. As is typical, these models go through behavior-based safety training: if the model does or says something that people don’t like, then the model is trained away from that. Examples include: ‘the model says false statements (intentionally or unintentionally)’, ‘the model shows signs of inappropriate or dangerous intentions (such as gaining power or additional resources)’ and ‘the model thinks or focuses on things that are not necessary to its tasks’.

In addition to these aspects, models have good situational awareness: from all the information they receive, they have a pretty good picture of their environment, i.e. the AI organization and their role in it. In particular, facts such as “the model is evaluated on the basis of its outputs” and “the model is monitored for potential bad behavior” are not well-hidden secrets.

So it’s no wonder that an organization can make AI look good on the surface: AI is trained to behave well in the eyes of people, and it knows what kind of behavior people expect. Thus, it learns to behave as the training signal pressures it to – if not, then by training more, the training process will soon find a model that does.

As we have discussed, behavioral training does not always remove undesirable thinking or behavior, but only suppresses it. Training out the visible deception causes the model’s deception to be more subtle. Training also encourages other undesirable behavior, examples include sycophancy, not mentioning particular information, and optimizing metrics in unintended ways. In addition, outcome-based training pushes the model away from fully legible thinking: a text that reflects one’s own ideas in detail is not the most effective or cheapest way to arrive at workable solutions.

The model’s externally visible behavior tells us less and less about what is happening inside the model, and our training methods are not doing what we optimistically hope they would do.

New situations. The environments the model encounters change. Perhaps the organization will take the next leap in automation and give the model more action space. Perhaps the organization will deploy the model for general use, and the model begins to be used globally for a variety of purposes. Maybe an outside party attacks the organization and steals a copy of the model.33

In the past, the AI has behaved well. This behavior has been based on both the training given to the model and its perception of its environment. Thus, as the environment changes, the behavior of the model might be expected to change: the model will generalize in some way to the new environment, and this way will not be “the model will act exactly the same as before, doing only good things”.

Given that the model has been trained to solve even long-term problems within its organization, it may well plan further into the future and set its sights on a larger-scale goal. And the model can still use the cognitive abilities it has – it just uses them for different things than before – and it can plan how to get things done. These skills include the training-relevant ability to keep things hidden and predict how people would react to the model’s actions. Thus, the end of the story is not “AI does obvious bad things and people go and shut it off”.

Needless to say, I don’t believe every detail, or indeed this story in general, will happen in reality. This is meant to be an illustration of how threats could take place in practice if not much effort is made to mitigate them.

Q: “What other scenarios are possible?”

Here are a few places where the story could have been told differently:

In the story, the model’s arrival in the new situation was the result of an external actor, not the model itself. However, models can also seek to extend their own influence: if models are trained to solve long-term, large-scale problems, thoughts about the limitations of one’s options and extending them are quite natural.

I framed the story “mundanely” as the model’s misgeneralization in a new environment. Generalization issues are ubiquitous in deep learning and so misgeneralization is to be expected. The story can also be looked at from a goal-based perspective: If models are trained to solve long-term, large-scale problems, they could well have internally represented goals related to the tasks assigned. From this perspective, a model would competently execute undesired plans as a result of poorly assigned goals.

The AI organization might notice that the model is doing something really bad, figuratively triggering a fire alarm. Again, there are a few ways the story might unfold. Perhaps the organization takes the problem seriously by, for example, discontinuing its use (and certainly not offering it for public use) and the risks are avoided – for now. There are also more cynical views: it would be far too expensive to disable AI altogether, so instead you go about patching the problem and controlling the risks with the methods you have, everything looks good on the surface for a while, and then similar problems appear elsewhere.

Perhaps at the end of the story, the AI will set out on its own to carry out its intentions, but this isn’t that bad: Either the model is not “trying” to do anything completely catastrophic, or people are aware of the AI and ultimately succeed in containing it. A warning shot has been fired, with more capable models it could have been worse, and the question is how we learn from the error. Perhaps the damage will be great, there will be a serious response and this will lead to (hopefully good) measures to reduce the risks of AI. Or maybe this is just one example of misalignment among dozens of others, which didn’t really cause any great harm, and it’s not really clear whether the AI was “trying” to do any harm, so no major changes are needed.

And as I mentioned at the beginning of the text, I am largely focusing on the risks posed by AI posed as an autonomous actor. Risks from misuse of AI and systematic risks posed by the increasing use of AI are also realistic, even though I have not discussed them here. Regarding societal risks, I refer the reader to Paul Christiano’s articles What Failure Looks Like and Another (outer) alignment failure story and Andrew Critch’s text What Multipolar Failure Looks Like, and Robust Agent-Agnostic Processes (RAAPs).

Ultimately, reality will probably be something else.34 Hopefully in a good way.

8. Solutions

Q: “What can be done about the threats posed by AI?”

I want to emphasize that the current situation is serious enough to warrant exceptional measures. “We are rapidly building AIs that are smarter than humans without knowing what we are doing, risking everyone’s lives” is not a normal state of affairs. I’m for example sympathetic to Yudkowsky’s description of the seriousness of the situation in Pausing AI Developments Isn’t Enough. We Need to Shut it All Down.

But I’m not here focusing so much on the governance or social side of things, because I’m not the right person to talk about them. Instead, I will list here some of the more technical directions that, if worked on, will put humanity in a better position.

1: Interpretability i.e. “explaining how AI systems work”, approaches including mechanistic explanations of the inner workings of the model35, the development of models during training36 and externalizing models’ thinking to interpretable form37.

2: Control38 i.e. “making sure that the models cannot cause bad things”. A few ideas for doing this:

- Using weaker, more trusted models to monitor the activities of more capable models, alerting humans about suspicious situations

- Break tasks into small, isolated chunks instead of tackling larger, more open-ended problems

- Isolating the model itself and keeping its weights safe

3: Evaluating capabilities39 and especially dangerous capabilities. Measuring many open- ended, multi-step tasks and abilities is difficult and laborious. Measuring subtle capabilities, such as the model’s situational awareness, requires careful design.

4: Designing and implementing responsible scaling policies40.